One of the key themes from our recent meeting with the CEO of one of the largest global asset managers was the substantial evolution in the traditional view of investing in public markets versus private markets.

Has ‘safe’ investing become ‘risky’ investing and vice versa?

Traditionally, public markets were perceived to be ‘safe’ while private markets were perceived to be ‘alternative’ and therefore more risky. This notion comes as no surprise, because over certain historic periods the data shows positive performance in public equities:

- for example an investment in the S&P500 index in the period 1994 to 1999 (highlighted below) would have generated juicy returns of between +20% to +49% per annum; and

- the period 2009 to 2021 (highlighted below) also shows strong annual performance.

This has substantiated the impression that “nothing can really go wrong” in public markets.

Beginning in the 80s and 90s, private market investments made headlines when companies acquired by Private Equity and burdened with debt fell into insolvency and required restructuring. This mainstream media perspective classified Private Equity as ‘risky investments’ with both high upside and high downside potential. But is this true today?

Over the last 20 years, Private Equity has evolved significantly, and its financing structures have changed considerably since its inception. Mainly due to regulatory reasons and a general higher risk aversion, banks are no longer able to provide the high levels of debt that were common in the 80s and 90s. More recently, banks have been replaced by large private credit managers who are pricing credit risk aggressively, resulting in naturally lower debt levels.

Private Markets, including both Private Equity and Private Credit, have matured over the last 20 years and, in our view, have become less risky than they were in the past.

Over the same period, public equity markets have become very expensive when measured by price-to-earnings (P/E) multiples. A P/E multiple represents the price an investor is willing to pay per unit of earnings of the underlying company. This multiple has increased substantially from around 7x in 1980 to over 25x today.1 Why would an investor be willing to pay $25 for one unit of earnings? No question, we would prefer to pay just $7. Do we really think that today we are looking at higher growth prospects or higher quality of earnings than in the 80s to justify a price of $25?

Considering the record debt levels of our governments today and the costs associated with the energy transition and investments in infrastructure and security & defence, we have serious doubts about the prospects of public equity markets at these price levels. In our view investors are no longer compensated for the risk they are taking in public markets.

So investors’ allocations in public equity markets, in our view, are no longer based on receiving a share of earnings at a fair price but rather on the expectation that the next investor will be willing to pay a higher price for their share later on. What is investment and what is speculation, then?

What we see is long-term inflation instead, not long-term growth. Can we possibly conclude that today public markets are no longer ‘safe’ and private markets are no longer ‘risky’?

Perhaps. However, we believe it is much more important to assess specific asset classes within public and private markets to determine their attractiveness based on risk profiles.

The Hidden Concentration Risk in Public Markets

Every investor seeks diversification. We are told that market sizenumber of market participants)should enhance diversification, leading to evenly distributed exposure to both ‘good’ and ‘bad’ companies. So, let’s examine the current state of large public equity markets:

1) The Declining Number of Public Companies

The number of public market participants appears to have declined by 38%. Historically, the U.S. had a much larger pool of public companies for investors to choose from. In the 80s and 90s, there were more than 6,500 domestic listed public companies in the U.S.,2 whereas today the number is just above 4,000. “Why is that?Companies apparently find it more attractive to stay private rather than go public. No surprise. This trend is not just a U.S. phenomenon but a global one. Currently, 87% of companies in the U.S. with revenues over $100 million are private. As an investor, why not seek exposure to the growth and innovation of these private companies instead of public ones?

The trend is likely to continue, as the decision for a company CEO and shareholders to stay private is logical and reflects the broader evolution in how companies seek financing and growth today. Capital from private sources has never been so attractive in terms of available volume, flexibility, and transaction certainty.

2) The Increasing Concentration of ‘Good’ Public Companies

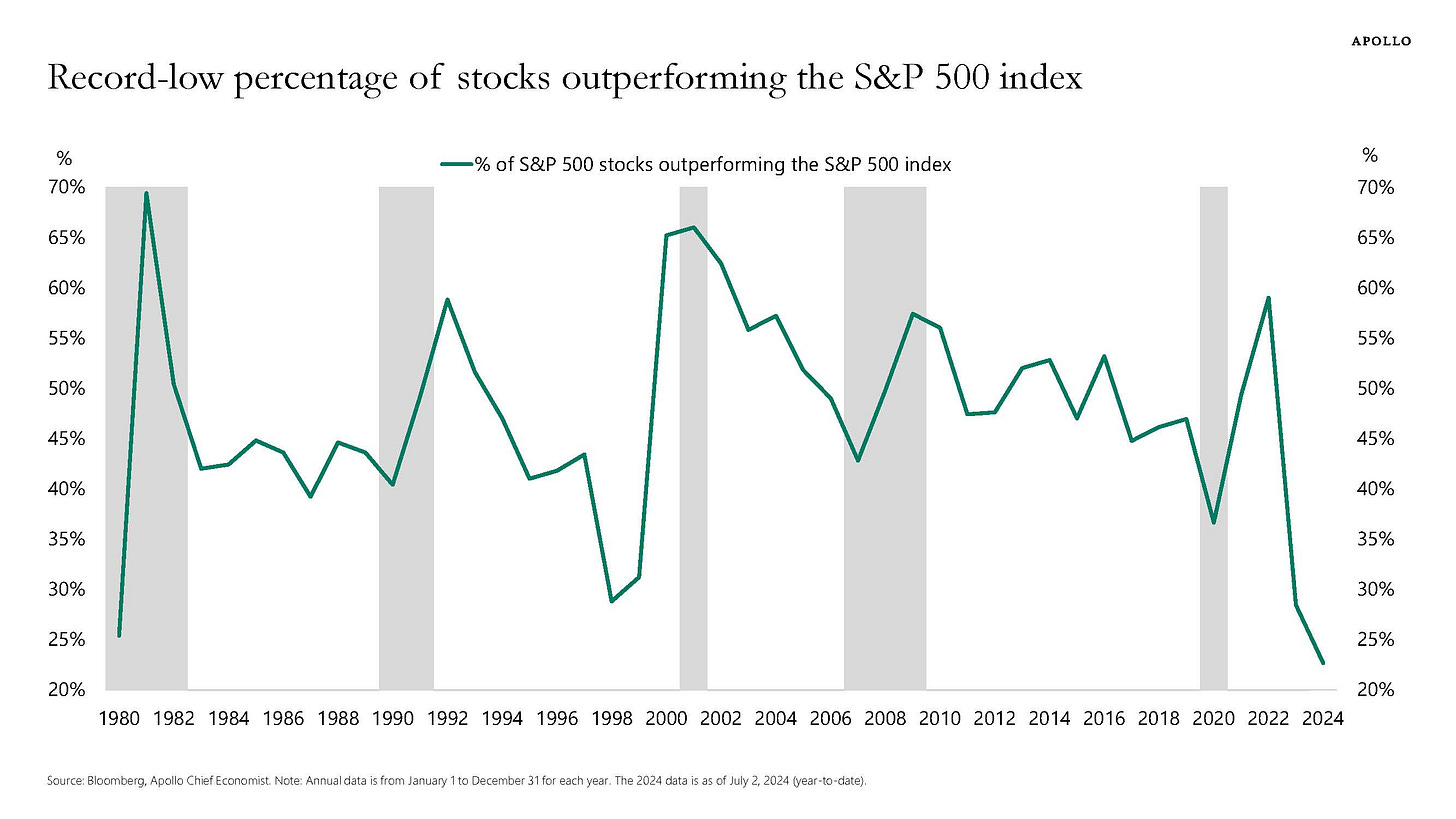

In addition to a shrinking universe of public companies, an even riskier trend can be observed: the concentration of public market performance is increasing significantly. This is far from the desired evenly distributed exposure to ‘good’ and ‘bad’ companies. Within the largest public market, the U.S. S&P500, the winners are highly concentrated among around 20% of the market participants, down from 60% 20 years ago and well below the typical historical range of 45-55%.

Our conclusion: Risk reduction through diversification in public markets has become unrealistic. The number of investment options is shrinking, and within that universe, the number of strong performers is also in decline. Public markets essentially come down to a few big bets. Private markets, on the other hand, offer a much larger universe to choose from. While this doesn’t necessarily make each investment safer, it does provide more choice and opportunity to select investments with less risky profiles and to ensure broad exposure. These factors will reduce portfolio risk.

The Asset-Liability-Mismatch at Banks – A Focus for Regulators

At its core, the financial system is designed to meet various financing needs, such as creating long-term infrastructure projects, financing the energy transition, ensuring continued innovation, and developing critical infrastructure like data centers, smart grids, power, logistics, and security. These are long-term, multi-year investments that require a stable source of capital. Traditional banks however, which primarily operate on short-term arrangements on their liability side, are restricted by regulations, such as the Basel III capital requirements, from financing such long-term projects on their asset side.

For example, the dependency on short-term deposits as a business model has repeatedly led to bank failures, such as Lehman Brothers, Northern Rock or Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and systemic crises such as the 2008 financial crisis. Therefore, these financing needs must be met by other sources, such as private markets.

The growing liability-asset mismatch in the financing system has significantly contributed to the creation and growth of private markets as an investment arena. Simultaneously, it has reduced the availability of balance sheets within the banking system for such investments.

The Choice of Long-Term Investors

While banks contend with an inherent asset-liability mismatch in their business model, private investors frequently face a similar dilemma. They may have long-term liabilities, such as saving for retirement or paying off a mortgage, while investing in short-term assets. However, investors have options. They can choose to invest in:

- daily liquid securities which are traded on an organised exchange; or

- long-term securities which can be accessed mostly in private markets.

In our view, private markets are better suited to match long-term liabilities with long-term assets, avoiding volatility in valuations and the systemic instability that can arise from using short-term funds for long-term investments.

The Cost of Daily Liquidity

Listing securities on an organized exchange is a costly undertaking. These costs encompass execution expenses, protection from legal liabilities, regulatory risks, and reputational risks for the issuer of listed securities. Ultimately, these costs are borne by the investor. We estimate that this ‘liquidity cost’ can reduce investor returns by at least 1% to 4% per annum. This represents the price an investor pays annually for having the option to buy or sell their investment holdings daily.

But with many long-term investors interested in maximising return while minimising risks, the cost of liquidity weighs very heavy on their returns. No surprise, a long-term investor in public markets may end up with a dismal performance of only 6% to 8% p.a. before inflation. We therefore believe the real return of 3% to 5% p.a. for an investor in public equity markets does not justify the risk taken. Why give up possibly up to 50% of real performance, if an investor does not use the possibility to trade on a second-by-second basis?

Public markets offer daily liquidity and immediate pricing transparency, which is appealing for those needing quick access to capital or instant valuations, but appalling for the overall return.‘Liquidity costs’ are a real loss and a drag on capital returns. In our view, for matching long-term capital needs, private market investing is more suitable.

How to access Private Credit?

Private Credit has evolved into an attractive form of private markets investing over the last 20 years. It comes in various forms, and diversification plays a crucial role in boosting returns, mitigating risks, and aligning with different investor cash requirement profiles. Investors must plan ahead and evaluate their desired duration of participation in Private Credit investments, as well as their anticipated cash needs.

Certain credit asset classes offer relatively higher liquidity, such as syndicated loans, supported by deep markets in the US and Europe. Additionally, direct lending, collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), and asset-based lending solutions are also prominent options in the Private Credit landscape.

The key lies in selecting the best-in-class credit manager from a vast universe and conducting thorough due diligence on the manager’s individual transactions. This process is essential to comprehending whether the risks assumed, the safeguards in place, and the returns generated are appropriately balanced.

As always, if you would like to discuss more about our own experience or share your experience on investing in private credit, please feel free to reach out to the team of Skin in the game.